We’ve mentioned before the Testing Effect – that its more efficient/effective to use your study time testing yourself rather than performing simple review.

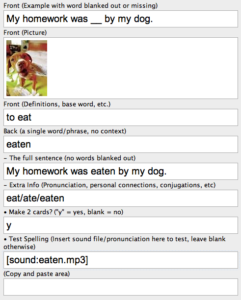

And that works great with flash cards – aka Leitner method and/or a Spaced Repetition Software-based system (like Anki). These flash cards serve as the base unit of knowledge. Which fits with the twenty rules of formulating knowledge, especially the fourth: Stick to the minimum information principle.

One fact per card. Base unit of knowledge. The building blocks, so to speak.

Any fact can be distilled into flash card form. The front side serves as the cue or the question, and the back side is the answer we judge our memory on.

But how do you build upon those basics? Can you still use the testing effect to apply to a more holistic or cumulative learning process? Are unit exams enough or do cumulative, much more far-reaching exams have merit?

So Much Of A Language Are The Basics

Many elements of language can be distilled down into basic facts.

In fact, modern second language acquisition research is seemingly headed more and more into that direction – now with new schools of thought pushing away from directly teaching grammar and seeing the benefit of using technology like spaced repetition software.

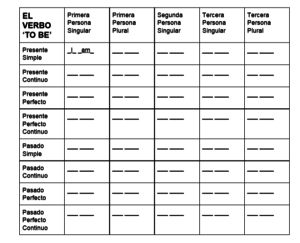

That means that previously grammar could only be taught with worksheets like:

Now they can be taught inductively with something more like:

Even pronunciation, with the ACA Method, is covered by first learning and understanding the sounds of the language individually.

The Basics Have Their Limits

But, Fundamentals makes up only a fourth of the ACA Method. And Mastery and Output require elements that can’t be put into pieces of software like Anki.

While lessons from Fundamentals give us sound practices like a selection of vocabulary learning that focuses on what native speakers use most frequently – not learning random semantic sets of words based on textbook unit chapters – still the whole is more than the sum of its parts…

A language is more than memorizing a section of vocabulary words and never revisiting them again.

Cumulative exams solve one of these problems – they ensure the old basics aren’t lost on a daily or weekly basis and are instead added as a base, to be built upon.

Because while we know that we need a big base of basics (a vocabulary of at least 600-1,000 words) to be able to even start to have any kind of meaningful communication, we also know that we need to know how to use those words in conjunction more than anything else.

The Studies Are In: Cumulative Testing Works

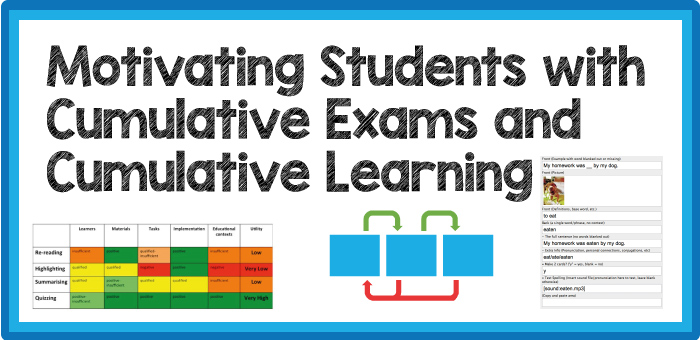

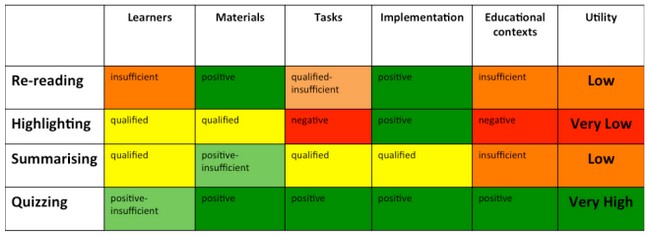

Low-stakes testing works. In 2013, cognitive science researches review hundreds of studies on pedagogical techniques and found just that:

They found that shorter and more frequent quizzes outperform longer and less frequent ones.

And that spacing the quizzes out lead to strengthened memories – perhaps due to the often-touted idea that more effort in the retrieval strengthens it. So the words chosen from older and older quizzes will prove more challenging and thus lead to strengthening their memory even more if successfully retrieved.

Summarizing their findings:

- Improves retention long-term

- Helps identify gaps in knowledge

- Causes students to learn more from next study session

- Provides feedback to instructors on where students need to work

- Provides feedback to students on self-study approaches (what words should they add/demote in their Leitner systems)

- Encourages students to study!

Oddly enough, our ACA Explorers actually look forward to these quizzes all week! I know this is strange behavior because I also taught high school chemistry! But good students are always anxious to show off their hard work and be praised for it. As they certainly should be.

How ACA Explorers Uses Cumulative Exams

The simplest way that ACA builds on the basics is by using cumulative exams. Each week, the word list we use is directly based on a thematic set of words selected from the 1,000 most frequently used words in English.

Thematic set?

For example, this week the words were: to stand, waiter, Friday, pain, back. Can you see a story in your mind connecting these words? Thus, thematic set.

A much better solution that simply learning all the days of the week at a time (semantic set), see: Grow Your Vocabulary Tree: Build Your Base (Pt. 1) for why learning words together like that can be problematic for any kind of fluency.

So we use cumulative exams because this week’s word bank for the quiz had not only those five words but also included words from the previous week’s words. So they had to study words from both weeks to ensure the learning has been cumulative from both weeks.

Each week, the word list will only get bigger. As long as they are doing the Leitner method appropriately, this shouldn’t be an issue. Especially considering we already have Explorers adding all kinds of new words on their own. (In fact, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to give a kind of challenge, a race to X words added….).

How ACA Explorers Uses Cumulative Learning

And while evaluation is actually a facet of learning, we use cumulative learning in a different sense by doing it outside of evaluation. We do live action stories, asking for action or verbal responses, based on Total Physical Response (TPR) actions we currently are using as well as actions we have learned in the past and retired.

In Teacher Says (a simple version of Simon Says), we add in actions for special events or student suggestions. Sometimes, we do throwbacks to these to see who still remembers. Amazingly, most do. And if they don’t, they have the option to easily follow along the action and re-learn it on the spot.

In Head, Shoulders, Knees, Toes we’ve done enough different versions where some of the more senior members remember a Neck, Chest, Elbows, Hands version we did as a student suggestion months back. There is real potential to use these TPR games to accumulate learning by doing more versions and randomly revisiting them at a later date.

The Golden Rule: Accumulate A High Base of Basics

There is such a strong front-loaded need to get to a base level of words in acquiring a second language that it needs special consideration.

Ideally, a student would throw all caution to the wind to get there. It is part of the Beginner’s Curve to a language learning that most never get past.

Either they give up at the beginning, or, as is most likely, they get dragged along unit by unit, never remembering the vocabulary they learned previously, because they are only worried about passing this week’s/this month’s test.

And while there is a lot of merit of achieving Mastery over your own domain first and not growing too fast (especially with the impressively difficult pronunciation considerations of the English language one has to take into account) but getting at least to 1,000 words makes all the difference.

Cumulative Learning Ensures the Foundation is Still Strong

This is what makes cumulative learning so important. The risk is great to forget words you recently learned. You need to treat your brain like it has a leak in it. You need to constantly tend to that leak, tend to those older memories to make sure they are still there and to strengthen them.

Otherwise the foundation, your base of words, will crumble before you can get to the top. To see the vista and to start to enjoy using your language.

Language becomes really fun on its own because you can really start to use it to communicate.

Language isn’t private. It is rooted in social interaction. You use it to communicate. So the quickest a language learner can move from a learner to a user the more likely they will be a user of it (and much better at it) ten years onward.

The best way to do that is to accumulate a lot of knowledge quickly. On your own, that is done using cumulative self-testing frequently. As a teacher, that is done by giving cumulative exams frequently!