An immersive experience in a country that speaks a language foreign to you – is the closest you get to being a baby all over again.

—

In ‘Learning a Language vs. Acquiring a Language’ we discussed Krashen’s Input Hypothesis, which differentiates learning from acquiring by postulating that acquisition is more in line with how everyone acquires their native language.

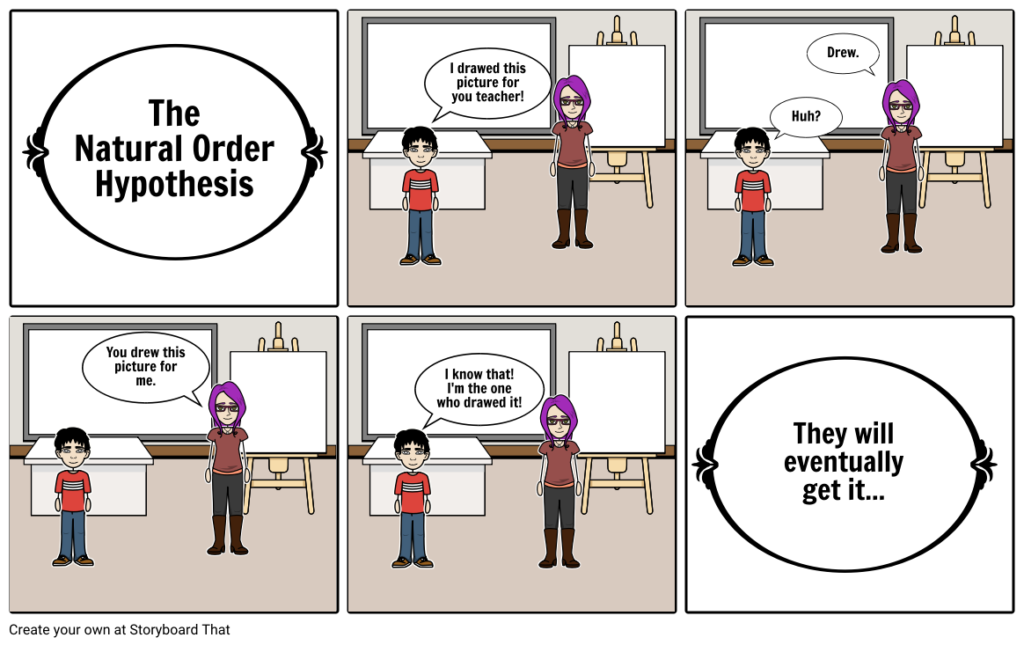

Krashen’s second postulate is that the acquisition process (especially grammatically) happens along a Natural Order, regardless of what language you are trying to learn, for first and second language ‘acquirers’ alike.

This he calls his Natural Order hypothesis.

Like children, we must learn to let go and go with the flow (the Natural Order). This acceptance allows us to relax, and walk a path of acquisition, knowing the path is a well-traversed, natural (perhaps even biochemical) one, and have fun while doing.

Krashen’s Input Hypothesis has five main aspects:

1- Learning/Acquisition Distinction

2- The Natural Order Hypothesis

3- The Monitor Model

4- The Input Hypothesis

5- The Affective Filter

Natural Order Hypothesis 101

What if some poor mother tried to speak to her child without using “a” and “the” until the child was 3 years old, waiting for the moment in the “order of acquisition” chart? Isn’t it obvious that the child would NOT suddenly begin to use “a” and “the” at that time? It took three and a half years of hearing the articles before the child’s developing semantic map gets around to actually mastering them!

An example: research tells us, in a great many of the world’s languages, a large amount children simply never learn to say ‘I run’ before ‘I am running’.

Krashen takes this logic and extends it to learning second languages. Just why is that do Spanish textbooks (or really any language textbook) teach us:

'Yo corro' - I run -before teaching- 'Estoy corriendo' - I am running

Let’s think about this for a second. Why is it that ‘corro‘/’run’ comes after learning ‘corriendo’/’running’?

Could it be one is easier to actually use (hear the difference/say the difference/see the difference/write the difference) than the other?

Comparing ‘runs’ to ‘running’ <> -ing vs. -s

Let’s see the conjugates of to run.

I run. You run. He/She runs. We run. They run.

So pretty much, you only have to change-from-the-infinitive-to-run …

aka conjugate the third-person singular tense:

He/She runs

So add an -s (for regular verbs) to the infinitive (the verb, as it is in its so-called “to” form: to run, to walk, to dine, to dash, …)

to run ... becomes... He/she runS

to walk ... becomes... He/she walkS

to dine ... becomes... He/she dineS

to dash ... becomes... He/she dashES

(uh oh! not regular! Still, pretty easy for most learners to come up with on their own…)

But Present Continuous Is Even Easier

But with the present continuous ‘running’, after learning the simple present of only one verb, you no longer have to conjugate anything at all.

I am...running You are...running He/she is...running We are...running They are...running

I am walking. She is eating. They are thriving. She is diving. He isn’t driving.

Sometimes with irregular verbs (thanks…English) the spelling is weird, but fortunately, the grammar and pronunciation remains easy (thanks, English).

I’ve certainly noticed it easier to teach the -ing morpheme earlier than the -s morpheme-.

That is to say, runnING before runS.

Colombians Find It Easier Too

Not to mention Colombians at the very least finding it much easier to say, even if they don’t have a fully developed velar nasal phoneme yet:

Even still, runnin or however it comes out, sounds much more clearer, and still communicates the message. I haven’t found that at all to be the case with the -s morpheme, especially in its third person form.

The S Sound in English Ain’t Even That Easy

The S sound however needs to be correctly sounded to properly communicate the message. And to do that you need to learn voicing, something a lot more difficult than a simple nasal velar.

In English, the -s ending has three possible pronunciations: /s/ 's sound': hats /hæts/ /z/ 'z sound': loves /lʌvz/ /ɪz/ 'short i'+'z sound': misses /'mɪ sɪz/ Source: Pronuncian.com

Natural Order Applied to Second Languages – Introducing The Order of Acquisition

Following the evidence Chomskey et al. showed for the Natural Order then, Krashen (1977) modified it somewhat with evidence from SLA literature, coming up with the Order of Acquisition that is surprisingly universal for first and second language acquisition alike:

'1. The “-ing” ending is first, with statements such as, “I eating.” 2. Next come the prepositions “in” and “on” (I sitting on Daddy.”) 3. Then plurals 4. Next come possessives “Birds is sitting on Daddy’s shirt!” 5. Then “a” and “the” begin to be used with regularity and accuracy. 6. Next is the tricky past tense. During ages 3, 4, and 5, they go through stages of past tense acquisition. They may say, “I goed,” or “I hitted.” What is happening is that they have internalized the “-ed” past tense and are now applying it generally.'

I am hitting and I was hitting will still come well before he hits. Some ESL (English as a Second Language) learners spend years studying English and still forget to add the -s morpheme on third person singular verbs.

How Best To Use The Order of Acquisition?

The order of acquisition, like anything in languages, is based on meaning.

Children, and adult acquirers alike, take on new word forms to convey meaning.

The grammatical features with the greatest amount of meaning to the child/student, are the first to be acquired. Which is why:

-Verbs, nouns, adjectives

Are acquired before things that don’t affect meaning:

-“Who” vs. “Whom” (many native English speakers still get this wrong…even though people don’t mess up I vs. me and the rule is the same)

regardless of how simple or difficult the rule may be

Letting the students struggle on their own will push them to acquire new forms as needed to convey meaning, to express themselves using real messages.

As long as they are receiving quality, comprehensible input, all of the grammatical forms will be fleshed out, in time.

This is where low quality input hurts big time. You can’t cheat input, and so if you are hearing a lot of bad grammatical features, your English might start to be riddled with features like:

“He was good people”

“He ain’t, he don’t tryna to”

Guiding Philosophy, Not A Rigid Template

But rather than use this as an outline for rigid textbook structuring, Krashen makes it clear it is rather evidence to point us towards keeping true to a Natural Mode of Acquisition, relying on comprehensible quality Input.

The Natural Order is like taking a raft ride down the river of grammar, instead of trying to swim upstream

But as we will learn when we discuss the Affective Filter, the Order of Acquistion makes us more comfortable in knowing that certain grammatical and/or phonetical structures are simplying beyond us at any given point in time. So just relax and to let things take their course naturally.

“In the long run we will all be dead”. Keynes knew this already in 1923. Of course grammar knowledge helps you to find shortcuts in the linguistic maze and to avoid going blindfolded down too many dead end alleys. Sure, being immersed and with all the time in the world, you acquire your first and second language. But in a class room twice a week? and your 3rd and 4th language? The human mind is able to learn everything else, so why not language?