Why is learning a language seemingly so hard? We’ve all already done it once, and when we were mere children with much smaller brains…so what gives?

In this blog, and on ACASpanish.com, I’ve mentioned several times that there exists a difference between learning a language and acquiring a language. You might feel I am being pedantic, but distinguishing these terms was not originally my idea, and as we will see, there are valid reasons as to why we should clarify what the difference actually is.

Learning a language is primarily what adult learners do when they take a traditional grammar-translation method and use it to improve their second (or third…) language skills.

Acquiring a language is primarily how children and how we all at one point went about the process of mastering our native language.

Learning is explicit. Acquiring is implicit. Learning is conscious. Acquiring is subconscious. Learning uses grammatical rules. Acquiring uses grammatical feel. Learning is useful but acquisition is necessary for true Mastery.

So can we use the same fundamentals of acquisition in regards to how children acquire languages as adults?

“The result of language acquisition is subconscious. We are generally not consciously aware of the rules of the languages we have acquired. Instead, we have a ‘feel’ for the correctness. Grammatical sentences ‘sound’ right or ‘feel’ right, and errors feel wrong, even if we do not consciously know what rule was violated.” Stephen Krashen

Krashen’s idea is that acquisition is more natural and leads to a much more well-rounded and capable language speaker. Krashen (and other prominent language-acquisition researchers like Noam Chomsky) argue that in our brains exist an innate Universal Grammar program that takes in auditory input and spits out language.

By following the model of how we all acquired our first language, Krashen argues that we can ‘learn’ a language much faster, more effectively, and enjoy the process much more.

Acquisition and the Input Hypothesis

Krashen’s Input Hypothesis has five main aspects:

1- Learning/Acquisition Distinction

2- The Natural Order Hypothesis

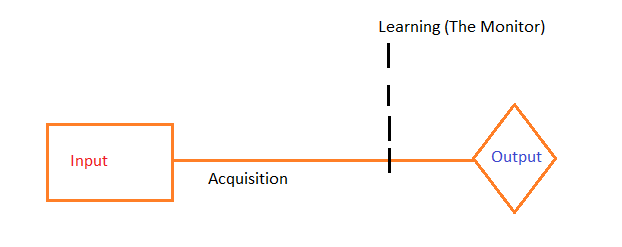

3- The Monitor Model

4- The Input Hypothesis

5- The Affective Filter

Krashen’s Input Hypothesis came about in the 1970s based on Noam Chomsky’s work into first language acquisition. Krashen sought to learn how everyone learned a language already and apply it to Second Language Acquisition (SLA).

This new model then relied on copying how children acquired their native languages and on how language classes could be facilitated to provide for structure based on a more natural acquisition model.

Input, Input, Input

How do children acquire languages? By listening! In fact, babies are exposed to thousands of hours of quality input in their native language before they speak a single word (often referred to as the Silent Period).

Krashen clearly distinguishes all input from comprehensible input. That is, like I said in The Best Input For Second Language Acquisition you need to actually understand (most) of what you are reading or hearing for your brain to be able to process it.

Comprehensible Input = i+1

Krashen, and other researchers, put the figure of comprehensible at around 95%. So if the page has 100 words on it, you’ll want to already understand 95 of them. The other 5 will slowly be pushed into your subconscious brain, acquired through context. You’ll have a more intuitive feel for words acquired this way and be able to use them with more fluent, masterful speech.

The idea of i+1 is to always be reaching, but only slightly. Again, it coincides with the idea of Flow I discussed in (Outdoor Language Classes In the Park: Why We Do What We Do Where We Do It). Don’t make it too easy yet not too hard either. 95% or around thereabout will make it enough of a challenge while still being enjoyable and meaning you won’t have to sit flipping through a dictionary instead of enjoying your Spanish (or English, etc) soap opera or romantic novel…

Is There a Benefit To Learning?

While Krashen points out that there are small benefits to learning a language, it is really only in a context that could help someone provide self-feedback on their own speaking or writing productive output. That self-monitoring Krashen calls the Monitor.

Having learned the appropriate conjugation for a verb tense, your own Monitor might ‘overhear’ an error in your thought patterns and be able to correct before, or immediately after, becoming ‘output’ aka being spoken.

The Real Problems of Learning versus Acquiring

Learning however, as Krashen tells us, does not become acquisition. And in many cases, it can do us a disservice. We can easily go down the wrong path and end up with bad habits (pronunciation, strange grammatical mistakes, false cognates, semantical set errors, much slower and less fluent speech ability, etc.).

Most likely, as with happens with most people that try to learn a language, we will just get frustrated with our progress, or lack thereof, and quit. Filling out grammar worksheets is just not fun. Communicating with real messages should always be the goal with language learning, so why not copy the model that gets us there the fastest?

The idea isn’t to learn a language. It is to get slowly used to it.

“Language acquisition occurs only when comprehension of a real message occurs and when the acquirer is not on the defensive.” Krashen

Pingback: The Monitor Model – Self-Correction and Acquiring/Learning A Language

Pingback: Coping with Chaos – Ambiguity Tolerance: The Life Lesson Language Learning Teaches Us

Pingback: Don’t Learn A Language. Get Used To It.