“Knowing a language rule does not mean one will be able to use it in communicative interactions.” (Brown 2000)

“Conscious learning can only be used as a monitor or an editor” (Krashen 1983)

As we discussed in Learning a Language vs. Acquiring a Language :

-Learning a language is traditionally the realm of adults and the result of conscious and explicit processing, focusing on form.

-Acquiring a language, on the other hand, is traditionally the realm of children and the result of subconscious and implicit processing, focusing on meaning.

Acquired language then can be used at any point in automatic processing. The goal is to make all of our language processing automatic – speak a language as if it were your mother tongue.

Not to translate, but to think in your second language.

What about learned material? Is it a waste? Will learned material ever be able to be acquired and ‘shifted over’ to automatic processing? Yes, but not necessarily.

Knowing vs. Using

Knowing Too Much – How It Hurts

As someone that has spent time ‘learning’ as well as ‘acquiring’ Spanish, I am fully aware of knowledge I have that is almost too meta to be used in automatic processing.

- Certain grammatical forms (the more complicated subjunctive rules)

- Gender cases (reminding myself of the exceptions like el tema)

- Specific pronunciation issues (raro may always come out raro when I say it…)

- Semantic sets learned together that only complicate things (not as bad anymore, but used to have to list out all the days of the week [Lunes, Martes, Miércoles, Jueves, Viernes, Sábado, Domingo] in order to say the one I wanted)

- And plenty of false cognates (atender and asistir – the opposite of what they sound like they should be in English)

This is because I learned Spanish before acquiring it. Granted, I learned it while living in Spain, but the traditional-style classes complicated things. But sometimes, it can ‘help’, depending on your goals…

Knowing Too Much – How It Helps

- It helps me teach Spanish

- As a result of knowing about the language, I can instruct new students of Spanish on the why of a certain new word form, order, case, or spelling.

- Having gone through both paradigms (learning and acquiring), and as a result having faced all the traditional pitfalls and obstacles along the way, I can help lay out an effective plan and methodology (The main reason ACASpanish is Gringo Lessons + Native Speakers)

- It helps me teach English

- The more I know about the intricacies of Spanish (or any language for that matter), the more I take a look at my own natively-acquired language, and the more I actively learn about it, helping me play both roles as a teacher (especially important with the Fundamentals)

- It started me off as a Writer over a Speaker

- My Spanish writing skills, until very recently, have grossly outstripped my Spanish speaking skills

- It gives me a Monitor

- Krashen’s Monitor Model gives some use to learned language knowledge

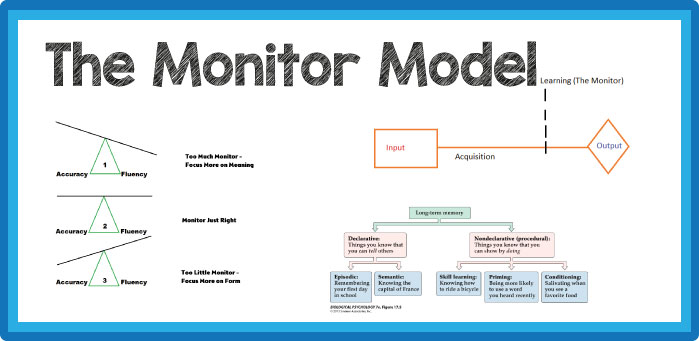

The Monitor Model

Knowledge acquired by conscious learning is able to be used consciously – a Monitor (or Editor) that watches over our Output (Speaking, Writing) to ensure it is Accurate.

This happens:

-Before Output (before anything is Spoken, Written)

-With a slight pause (or an uhhhh)

-Self-correction after saying or writing something wrong (or at least we feel it to be)

We will come to see (by discussing amnesia of all things) how The Monitor, with its source of explicit knowledge, takes residence in a very specific part of the brain, and how its quite different for implicit/subconscious knowledge you’ve acquired.

Conditions For Using the Monitor

- Knowledge

- Focus on Form

- Time

Knowledge

Probably the most difficult condition. The user must know the rule, the grammatical or spelling or pronunciation rule, etc., and know it explicitly – that is, be able to express it verbally.

If you don’t know the rule well enough, you likely aren’t going to be confident enough, and your self-feedback system of The Monitor might not even pop up to tell you that you just said it wrong…

Focus on Form

The user is going to have to be focused more on accuracy (form) than fluency (meaning). This is what slows down fluent speech, as you are quite literally using different parts of your brain in using The Monitor.

Time

How much time is available to think and consider? Clearly, this is less of a problem (or not a problem at all) when it comes to writing but speaking is an entirely different manner. A prepared speech is going to have different time constraints (not to mention a different Affective Filter…) than an improvised dialogue between friends.

Over-reliance on The Monitor is what, time and time again, short-changes any language student into being afraid of speaking: with so much focus on accuracy, you never train Mastery, and so never acquire an ease with speaking your new language.

You overall will speak slower and take much longer to reply.

Accuracy/Fluency

So just how much should we rely on the Monitor Model, if we meet all the conditions?

Ideal use of the monitor is somewhere in a balance. Using it just enough to ensure accuracy is high, but not too much.

Ideally, I think a heavier balance on (3) is much better than the (1) situation, especially at the beginner.

Follow a young child around and ask yourself how much they are worrying about accuracy. Not as much. And in fact neither are their caretakers. Many studies have shown how parents and caretakers only correct children’s speech when it is simply inaccurate or when they say a ‘forbidden’ word.

-Daddy go work – Isn’t going to get corrected to the proper form (Daddy goes to/is going to work now)

-Daddy be work – Is going to get corrected to the proper meaning because Daddy isn’t work but he is going there…

Explicit and Implicit Knowledge – Knowing vs. Using

Explicit – learned – things we know that we can talk about

Implicit – acquired – things we know (can ‘use’ automatically) that we can’t talk about

Most of what we have learned about the brain and memories has come from research on brain dysfunction – mostly from studying those with brain injuries/disorders.

We know there exists a physical difference between implicit and explicit knowledge – they are stored in a different part of the brain!

Anterograde Amnesia vs. Retrograde Amnesia

Brain injuries causing anterograde amnesia – the loss of the ability to form new memories, but retaining implicit knowledge and ability to learn new skills – occur in the hippocampus, which suggest the hippocampus plays a central role in new memory encoding/short-term memory processing.

Retrograde amnesia, however, is the loss of old, long-term memory, before the brain injury occurred. Damage is usually seen in areas of the brain other than the hippocampus, such as the temporal and frontal lobes, as well as the prefrontal cortex, suggesting these areas play a central role in long-term memory storage.

Expressive aphasia, caused by damage to Broca’s area found in the frontal lobe, is a deficit in language production, an inability to express yourself using your mother tongue.

Therefore, learned language (explicit) is processed in the hippocampus and sent off to the frontal lobes/prefrontal cortex for long-term memory storage and automatic processing (implicit).

Short Term to Long Term – From Explicit to Implicit Knowledge

Is it possible to mediate between short term and long term memory?

Clearly, it must be. Without this process happening, we would never be able to ‘acquire’ anything at all.

But what if an item was ‘explicitly’ learned?

For example: can the old mnemonic of:

"This and these have 'ts', That and Those don't" -Este/esta - this; Estes/estas - these -Ese/esa - that; Eses/esas - those

Be pushed as implicit knowledge to areas of my brain, allowing me to use these automatically with a good balance of fluency/accuracy, without having to stop and Monitor?

Shifting From Knowing to Using: Is It Possible?

“Knowing a language rule does not mean one will be able to use it in communicative interactions.” (Brown 2000)

Krashen and followers of the Input Hypothesis would argue that it cannot. That there is simply no interface between acquired language and learned language. The only pseudo-interface, therefore, would be the Monitor Model, which exists to access but not convert explicit, learned knowledge.

So while useful, especially if you want to get a jump start in actually speaking/writing and being understood, what you explicitly learn is only going to have to be implicitly acquired later on.

Concluding Remarks

Acquire more than you learn, so your language use is automatic, you have a feel for grammar, and things either sound right or sound wrong. Unless you are gunning to become a linguist, learning too much about a language will only serve to make it more difficult to speak it fluently.